Industrial

agriculture

The links between industrial agriculture and climate change are

twofold. On the one hand, industrially produced food systems are

energy-intensive and fossil-fuel based, and thus contribute significantly to

climate change. On the other hand, the crops grown in the genetically

homogeneous monocultures that are typical of chemical farming are not resilient

to the climate extremes that are becoming more frequent and more violent.

Industrial agriculture originated in the 1960s when petrochemical

companies introduced new methods of intense chemical farming. For the farmers

the immediate effect was a spectacular improvement in agricultural production,

and the new era was hailed as the "Green Revolution." But a few

decades later, the dark side of chemical agriculture became painfully evident.

It is well known today that the Green Revolution has helped

neither farmers, nor the land, nor the consumers. The massive use of chemical

fertilizers and pesticides changed the whole fabric of agriculture and farming,

as the agrochemical industry persuaded farmers that they could make more money

by planting large fields with a single highly profitable crop and by

controlling weeds and pests with chemicals. This practice of single-crop

monoculture entailed high risks of large acreages being destroyed by a single

pest, and it also seriously affected the health of farm workers and people

living in agricultural areas.

With the new chemicals, farming became mechanized and

energy-intensive, favoring large corporate farmers with sufficient capital, and

forcing most of the traditional single-family farmers to abandon their land.

All over the world, large numbers of people left rural areas and joined the

masses of urban unemployed as victims of the Green Revolution.

The long-term effects of excessive chemical farming have been

disastrous for the health of the soil and for human health, for our social

relations, and for the natural environment. As the same crops were planted and

fertilized synthetically year after year, the balance of the ecological

processes in the soil was disrupted; the amount of organic matter diminished,

and with it the soil’s ability to retain moisture. The resulting changes in

soil texture entailed a multitude of interrelated harmful consequences — loss

of humus, dry and sterile soil, wind and water erosion, and so on.

The ecological imbalance caused by monocultures and excessive

use of chemicals also resulted in enormous increases in pests and crop

diseases, which farmers countered by spraying ever-larger doses of pesticides

in vicious cycles of depletion and destruction. The hazards for human health

increased accordingly as more and more toxic chemicals seeped through the soil,

contaminated the water table, and showed up in our food.

In recent years, the disastrous effects of climate change have

revealed another set of severe limitations of industrial agriculture. As Miguel

Altieri and his colleagues at SOCLA (the Sociedad Cientifica

Latinoamericana de Agroecologia) point out in a recent report, the Green

Revolution was launched under the assumptions that abundant water and cheap

energy from fossil fuels would always be available, and that the climate would

be stable. None of these assumptions are valid today. The key ingredients of

industrial agriculture — agrochemicals, as well as fuel-based mechanization and

irrigation — are derived entirely from dwindling and ever more expensive fossil

fuels; water tables are falling; and increasingly frequent and violent climate

catastrophes wreak havoc with the genetically homogeneous monocultures that now

cover 80 percent of global arable land. Moreover, the practices of industrial

agriculture contribute about 25 to 30 percent to global greenhouse gas

emissions, further accelerating climate change.

Our fossil-fuel based industrial agriculture contributes to

greenhouse-gas emissions in several distinct ways: directly through the fuel

burnt by agricultural machinery, during food processing, and by transporting

the average ounce of food over a thousand miles "from the farm to the

table"; indirectly in the manufacture of its synthetic inputs, e.g. of

nitrogen fertilizer from nitrogen and natural gas; and finally by breaking down

the organic matter in the soil into carbon dioxide (during large-scale tillage

and as a consequence of excessive synthetic inputs), which is released into the

atmosphere as a greenhouse gas. In addition, massive amounts of methane (a

greenhouse gas many times more potent than CO2) are released during large-scale

industrial cattle ranching.

The degrading of healthy organic soil by chemical fertilizers

and pesticides increases the soil's vulnerability to drought by reducing its

capacity to capture water and keep it available for crops. A further

devastating effect of the over-fertilization that is typical of current

chemical farming practices is the nutritional overload in our waterways, caused

by runoffs of agricultural nitrates and phosphates, which lead to oxygen

depletion in rivers and to so-called "dead zones" in the oceans,

which are no longer inhabitable by most aquatic life.

From a systemic point of view, it is evident that a system of

agriculture that is highly centralized, energy-intensive, excessively chemical,

and totally dependent on fossil fuels; a system, moreover, that creates serious

health hazards for farm workers and consumers, and is unable to cope with

increasing climate disasters; cannot be sustained in the long run.

DIFFERENT

CLIMATES IN THE WORLD

1)Tropics

2) Temperate

3) Tundra

4) Desert

WATER

Soil

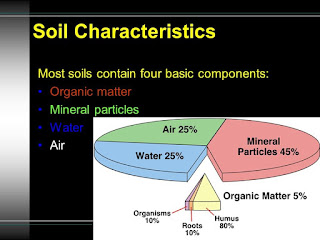

(i) The unconsolidated mineral or organic material

on the immediate surface of the Earth that serves as a natural medium for the

growth of land plants.

(ii) The unconsolidated mineral or organic matter on the

surface of the Earth that has been subjected to and shows effects of genetic

and environmental factors of: climate (including water and temperature

effects), and macro- microorganisms, conditioned by relief, acting on parent

material over a period of time.

A product-soil differs from the material from which it is

derived in many physical, chemical, biological, and morphological properties

and characteristics.

HUMAN

RESOURCES

Human

Resource Development is an important factor in capacity building and improving

the overall efficiency of functionaries involved in implementation, monitoring,

evaluation, research and extension programmes. Training is a major component of

Human Resource Development. Systematic training, planning, management and its

implementation by making best utilization of resources available within the

country helps in bringing about desirable changes in knowledge and upgrade

skills of extension functionaries associated with the process of agriculture

development. The training infrastructure has been created to meet out the

training requirements of all levels of extension functionaries, farm youth and

farmwomen. Looking into the importance of training in capacity building of

extension experts and farmers, this scheme is selected for the strengthening of

extension services and dissemination of agricultural technology to the farming

community.

IMPACT OF

CLIMATE CHANGE

The greenhouse effect

The earth is surrounded by an atmosphere through which solar

radiation is received. The atmosphere is not static but contains air, in

constant motion, being heated, cooled and moved, water being added and removed

along with smoke and dust. Only a tiny proportion of the sun's energy

reaches earth and some of this is reflected back into space (from clouds etc.).

When the radiant energy reaches the land surface, most of it is absorbed, being

used to heat the earth, evaporate water and to power photosynthetic processes.

The earth also radiates energy but, because it is less hot than

the sun, this is of a longer wavelength and is absorbed by the atmosphere. The

Earths atmosphere, thus acts like the glass of a green house, hence the

'greenhouse effect'.

Global warming

The term

used to describe a gradual increase in the average temperature of the Earth's

atmosphere and its oceans, a change that is believed to be permanently changing

the Earth's climate.

No comments:

Post a Comment